Adult Development Theory

In recent years, more scholars and educators have come to emphasize the importance of adult development theory as a critical framework to use when promoting leadership development. Among others, Day et al. propose an integrative approach to leadership development based on adult development theory. They argue that leadership development occurs at three layers in a continuously dynamic way throughout one’s life span.

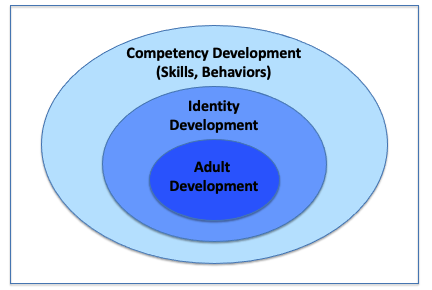

Three Layers of Leadership Development

NOTE. ADAPTED FROM AN INTEGRATIVE APPROACH TO LEADER DEVELOPMENT: CONNECTING ADULT DEVELOPMENT, IDENTITY, AND EXPERTISE. BY D. V. DAY, M. M. HARRISON, AND S. M. HALPIN, 2009, P. XIII.

The most outside layer is about the competencies of leaders such as skills, behaviors, and knowledge about problem-solving and decision-making. The middle layer concerns leader identity, which shapes their values and goals and influences their behaviors as leaders. If one does not think of oneself as a leader or aspire to lead, then there is little motivation or incentive to act as a leader and further develop leadership. The innermost layer is about the deepest psychological capacities related to how a person makes sense of herself, others, and the world. Adult development theory suggests that human development does not stop when one reaches adulthood, but rather continues (or at least has the potential to continue) throughout one’s life, and that there are foreseeable patterns or stages in how adults develop. Therefore, Day et al. contend that leadership development should focus on the inner layers of identity and adult development than on the outer, more visible layers of skills and behaviors. Especially given the greater complexity caused by the recent growing impact of technology and globalization, some scholars have even emphasized that people need to develop a more complex mindset for leadership. Thus, leadership development needs to focus on higher levels of adult development.

Some theories of adult development focus on one aspect of human development, such as Kohlberg’s moral development, Fischer’s cognitive development, and Fowler’s spiritual development. These theories, however, are not enough to explain and evaluate the comprehensive aspects of leadership development including cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. Instead, the most useful theory of adult development for leadership development is constructive development theory because it integrates the three dimensions of adult development (i.e., cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal development) into a larger framework. Recently, the constructive developmental approach has been most frequently used as a theoretical framework to study leadership.

Constructive Development Theory

Constructive development theory is a term joining two different schools of thought: constructivism and developmentalism. Constructivists propose that the world does not exist to be discovered, but that people create their world by discovering it. Humans make meaning through their own lenses. For example, two different people could experience the same event and interpret it in two different ways. Developmentalists believe humans grow and change over time and move into qualitatively different phases as they grow. Development can be accelerated or hindered by the individual’s life experiences. Constructive developmentalists thus believe that the systems where people make meaning grow and change over the course of action. Constructive development theory has provided the foundation for several models of adult development. Many are based on stage development theory, which posits that individuals move through different developmental stages over the course of their lives. As individuals transition from one stage to the next, the way in which they know the world broadens and leads to a qualitative evolution in meaning-making and mental complexity. Notable constructive developmental frameworks include Kegan’s subject-object balance, Loevinger’s ego development, Torbert’s action logic, and Cook-Greuter’s vertical growth and meaning making.

Although each constructive developmental theorist has articulated slightly different approaches to his/her theory around terms of stages and ways of describing the transition between developmental stages, there seems to be a great deal of overlap in the underlying logic of the stages, which makes cross-theory mappings possible. The table below describes one such cross-theory comparison. All the theories presented demonstrate a similar progression from a self-centered orientation, through a socially dependent orientation, toward an individually independent orientation, and finally into an ecologically inter-independent orientation. Each orientation is a qualitative shift in meaning-making and complexity from the orientation before it.

Stage Comparison of Four Constructive Development Theories

NOTE. ADAPTED FROM (COOK-GREUTER, 2021; JOINER & JOSEPHS, 2007; MCCAULEY ET AL, 2006) AND EXPANDED USING (LOEVIINGER, 1998).

Self-centered Orientation

People in the self-centered orientation can maintain an idea or belief over time. While they are aware that others have feelings and desires, however, empathy is impossible for them yet because the distance between their minds and others is so far. Children (and some adults) at this orientation are self-centered and see others as either helpers or barriers to achieve their own needs, interests, and desires.

Dependent Orientation

People in the dependent orientation have developed the ability to subordinate their desires to the desires of others. Their needs, interests, and desires, which were subjects to them in the previous orientation, have become objects. They can think abstractly, be self-reflective about their actions and the others’ actions. They can devote themselves to something greater than their own needs. They can internalize the others’ emotions and are guided by those people, communities, or institutions that they attach or belong to. The major limitation of this orientation is that when there is a serious conflict between important others, people in this orientation are torn into two and cannot find a constructive way to make a decision. People in this orientation do not independently construct self-esteem. Their self-esteem is entirely dependent on others. Research suggests that people typically transition into this orientation by adolescence or early adulthood.

Independent Orientation

Adults in the independent orientation have achieved all that those at the previous orientations have, but they now have established a self outside of its relationship to others. Those in the independent orientation are self-guided, self-motivated, and self-evaluative. They do not feel torn apart by the conflicts of those around them, because they have their own internal set of rules and standards. They can make their decisions and mediate conflicts by using their self-governing system. Unlike those at the self-centered orientation, those at the independent orientation feel empathy for others and consider others’ opinions when making decisions. Research suggests that adults typically reach this orientation by mid-life or later, if at all, and most adults are involved in the transition between dependent and independent orientations.

Inter-independent Orientation

Adults in the inter-independent orientation are very few. They have achieved the limits of their own inner system and the limits of having an inner system in general. People in this orientation are less likely to see the world as dichotomies or polarities. They are likely to believe that what we think of as black and white are just various shades of gray whose differences are made more visible by the lighter or darker colors around them.

Measuring Stages of Adult Development

As a constructive development theory, Kegan’s subject-object theory, Loevinger’s ego development theory, Cook-Greuter’s vertical growth theory, and Torbert’s action logic have substantial overlap. However, they use different measurement methods to define developmental stages, with Kegan using a structured interview method and the other three (i.e., Loevinger, Cook-Greuter, and Torbert) using a sentence completion test. Both methods are quite labor-intensive to score as compared with other psychometric tests that often use multiple-choice or fixed-answer methods. In return, more complex methods are thought to yield deeper and more valid results than the self-rated, fixed-choice methods.

Kegan and his colleagues developed the Subject-Object Interview (SOI) as a measure of orders of mind (or developmental stages) based on Kegan’s subject-object theory of adult development. The SOI is a 60- to 75-minute one-on-one interview. A trained and qualified interviewer sits with a participant and asks her about her recent experience on the topic relating to the word such as “angry,” “success,” “sad,” and “change” on 10 index cards. The interviewer follows the participant’s thinking until he/she reaches the edges of his/her own belief or understanding. The objective of the interview is to investigate the “structure” of the participant’s thinking rather than the “content” of her thinking. The interview is recorded and transcribed with consent from the participant. Two qualified evaluators independently assess the transcript of the interview and confirm the accuracy of the evaluation. Although the SOI has widely been assessed in terms of validity and reliability, it has not much been assessed in other languages. For example, there is no Japanese translation of the scoring manual and thus there are a very limited number of studies using the SOI in the Japanese context.

On the other hand, Loevinger developed a language-based instrument named the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT), which delineates eight stages of ego development originally designed to address women’s issues. The WUSCT includes 36 open-ended sentences that aim to measure a broad range of content: moral development, interpersonal relations, and conceptual complexity. An extensive body of research has provided substantial support for the conceptual soundness and validity of her theory and the WUSCT, not only in the English context but also in other cultures and languages. Cook-Greuter modified the WUSCT so that it could assess the later stages more precisely and developed her own measure named the Mature Adult Profile (MAP). Torbert also modified the WUSCT to assess the adult development of leaders based on his action logic framework. He replaced four of the sentence stems with work-related stems and named his measure the Global Leadership Profile (GLP). GLP is a little concise. It is composed of 30-stem questions.

Criticisms of Constructive Development Theory

There are several criticisms of the constructive developmental theory, because of the nature of the fact that it is a stage development theory. It posits that development takes place through the sequential, forward movement of one’s entire meaning-making system through stages of increasing complexity.

One of them is that the theory could be considered elitist because the later stages are considered “better” than the earlier stages. Kegan insists that the persons in the later stage are not better persons than those in the earlier stage, but they have a more complex meaning-making system. They are just different. Effective leaders are only required to operate at a stage that matches the complexity of the circumstance where they are working. Thus, later stages may not always be necessary.

Another criticism is the pragmaticism of the theory. Assessing one’s stage of development costs a lot and takes time. Sentence completion tests such as Torbert’s Global Leadership Profile (GLP) normally cost hundreds of dollars. Kegan’s Subject-Object Interview (SOI) is theoretically the most sophisticated measure, but it requires an interview of more than one hour and further hours to analyze and score each interview by two certified evaluators. Accordingly, it is virtually impossible to administer large-scale research at a reasonable cost. Because of the difficulty to collect large data samples, there are still limited numbers of literature. In addition, the majority of research has been of short-term duration, regardless of the fact that developmental movement takes time. Furthermore, almost all of the research was run by the developers of the theory and his colleagues. Therefore, the theory may lack independent validation and generalizability.

The last criticism is the inconsistency among the different assessment methods. Jones assessed 11 people using Kegan’s SOI and Torbert’s GLP and found there was an exact match between the two assessments for only three samples, whereas there were discrepancies between the two assessments for the remaining eight samples. SOI and GLP data are generated using quite different processes, so it may be possible that the two assessments do not necessarily reach the same result. Nevertheless, this discrepancy is still problematic for empirical research.

References

Brown, B. C. (2013). The future of leadership for conscious capitalism. CCANZ. https://consciouscapitalism.org.au/2015/03/17/the-future-of-leadership-for-conscious-capitalism/

Commons, M. L. (1990). Adult development: Models and methods in the study of adolescent and adult thought. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Cook-Greuter, S. (2021). Ego development: A full-spectrum theory of vertical growth and meaning making. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356357233_Ego_Development_A_Full-Spectrum_Theory_Of_Vertical_Growth_And_Meaning_Making

Day, D. V., Harrison, M. M., Halpin, S. M. (2009). An integrative approach to leader development: Connecting adult development, identity, and expertise. Psychology Press.

Fischer, K. W. (1980). A theory of cognitive development: The control and construction of hierarchies of skills. Psychological Review, 87(6). 477-531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.87.6.477

Fischer, K. W., & Pipp, S. L. (1984). Processes of cognitive development: Optimal level and skill acquisition, in Steinberg, R. J. (Ed.): Mechanisms of Cognitive Development, 45-80. W. H. Freeman.

Fowler, J. W., & Levin, R. W. (1981). Stages of faith: The psychology of human development and the quest for meaning. HarperCollins Publishers.

Harris, L. S., & Kuhnert, K. W. (2008). Looking through the lens of leadership: A constructive developmental approach. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29(1), 47-67. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730810845298

Helsing, D., & Howell, A. (2013). Understanding leadership from the inside out: Assessing leadership potential using constructive-developmental theory. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(2), 186-204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492613500717

Joiner, W. B., & Josephs, S. A. (2007). Leadership agility: Five levels of mastery for anticipating and initiating change. John Wiley & Sons.

Jones, J. A. (2015). Beyond Generosity: The Action Logics in Philanthropy. (Doctoral dissertation). University of San Diego, San Diego: CA. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Beyond-Generosity%3A-The-Action-Logics-in-Jones/79a8e0c26b612a036ca6f346b31a5186265ff6cb

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self. Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2009). Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock potential in yourself and your organization. Harvard Business Press.

Kohlberg, L. (1981). The philosophy of moral development moral stages and the idea of justice. Harper & Row.

Loevinger, J., & Wessler, R. (1970). Measuring ego development. Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers.

Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego development: Conceptions and theories. Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers.

Loevinger, J., & Hy, L. X. (1996). Measuring ego development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Loevinger, J. (1998). Technical foundations for measuring ego development: The Washington University sentence completion test. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Publishers.

McCauley, C. D., Drath, W. H., Palus, C. J., & O’Connor, P. M. G. (2006). The use of constructive-developmental theory to advance the understanding of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 634-653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.006

Murray, T. (2017). Sentence completion assessments for ego development, meaning-making, and wisdom maturity, including STAGES. Integral Leadership Review, 17(2).

Palus, C. J., & Drath, W. H. (1995). Evolving leaders. A model for promoting leadership development in programs. Center for Creative Leadership.

Petrie, N. (2011). Future trends in leadership development [white paper]. Center for Creative Leadership. http://integralleadershipreview.com/7264-nick-petries-future-trends-in-leadership-development-a-white-paper/

Petrie, N. (2014). Vertical leadership development–Part 1: Developing leaders for a complex world. Center for Creative Leadership.

Strang, S. E., & Kuhnert K. W. (2009). Personality and leadership developmental levels as predictors of leader performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 421-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.009

Tamura, J., Watanabe, R., & Watanabe, R. (2019). Measuring effectiveness of a leadership basics course in a Japanese university: Using the adult development theory by Professor Robert Kegan at Harvard University. Hogaku Kenkyu (Journal of Law, Politics, and Sociology), 92(3): 1-29.

Torbert, W. R. (2004). Action inquiry: The secret of timely and transforming leadership. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Torbert, W. R. (2019). Brief comparison of five developmental measures: the GLP, the MAP, the LDP, the SOI, and the WUSCT. The Library of William R. Torbert.